‘State Ibuism’ is not dead, it’s not even past

The name Julia Suryakusuma is a familiar one for readers. Through her columns, she touched upon a wide range of social and political topics and has contributed some of the most succinct and insightful commentaries on contemporary Indonesia available. Not all readers will realize that Julia’s unrelenting humanity, incisiveness and humor have a deep and influential history in the social sciences and beyond. Permit me a personal example. In January 1997, I was in the midst of pursuing my Ph.D. degree in cultural anthropology at Stanford University. I had been working with gay, lesbian and transvestite Indonesians since 1992 and knew I wanted to study their lives for my dissertation thesis.

Six months before beginning my long-term fieldwork, I came across the essay “The State and Sexuality in New Order Indonesia” in the book Fantasizing the Feminine in Indonesia (Laurie Sears, editor: Duke University Press, 1996).

The essay, in which Julia introduced state ibuism to encapsulate how the New Order government used ideologies of gender and sexuality as a form of social control, was the intellectual equivalent of a bolt of lightening in my head.

Vague ideas concerning the relationship between sexuality and nation became clear, and I could formulate the goals of my research in a new manner.

A glance of the subtitle of my first book — The Gay Archipelago: Sexuality and Nation in Indonesia (Princeton University Press, 2005) — not to mention the citations to Julia’s work within it, reveals the depth of this intellectual debt.

Six months before beginning my long-term fieldwork, I came across the essay “The State and Sexuality in New Order Indonesia” in the book Fantasizing the Feminine in Indonesia (Laurie Sears, editor: Duke University Press, 1996).

The essay, in which Julia introduced state ibuism to encapsulate how the New Order government used ideologies of gender and sexuality as a form of social control, was the intellectual equivalent of a bolt of lightening in my head.

Vague ideas concerning the relationship between sexuality and nation became clear, and I could formulate the goals of my research in a new manner.

A glance of the subtitle of my first book — The Gay Archipelago: Sexuality and Nation in Indonesia (Princeton University Press, 2005) — not to mention the citations to Julia’s work within it, reveals the depth of this intellectual debt.

I knew the essay came from a much larger study based upon research conducted in the mid-1980s from a Master’s thesis focusing upon the new order’s Family Welfare Movement, or PKK as it is commonly known. For over 20 years, this thesis has circulated informally among Indonesianists worldwide, and many have expressed a strong desire to see the thesis formally published.

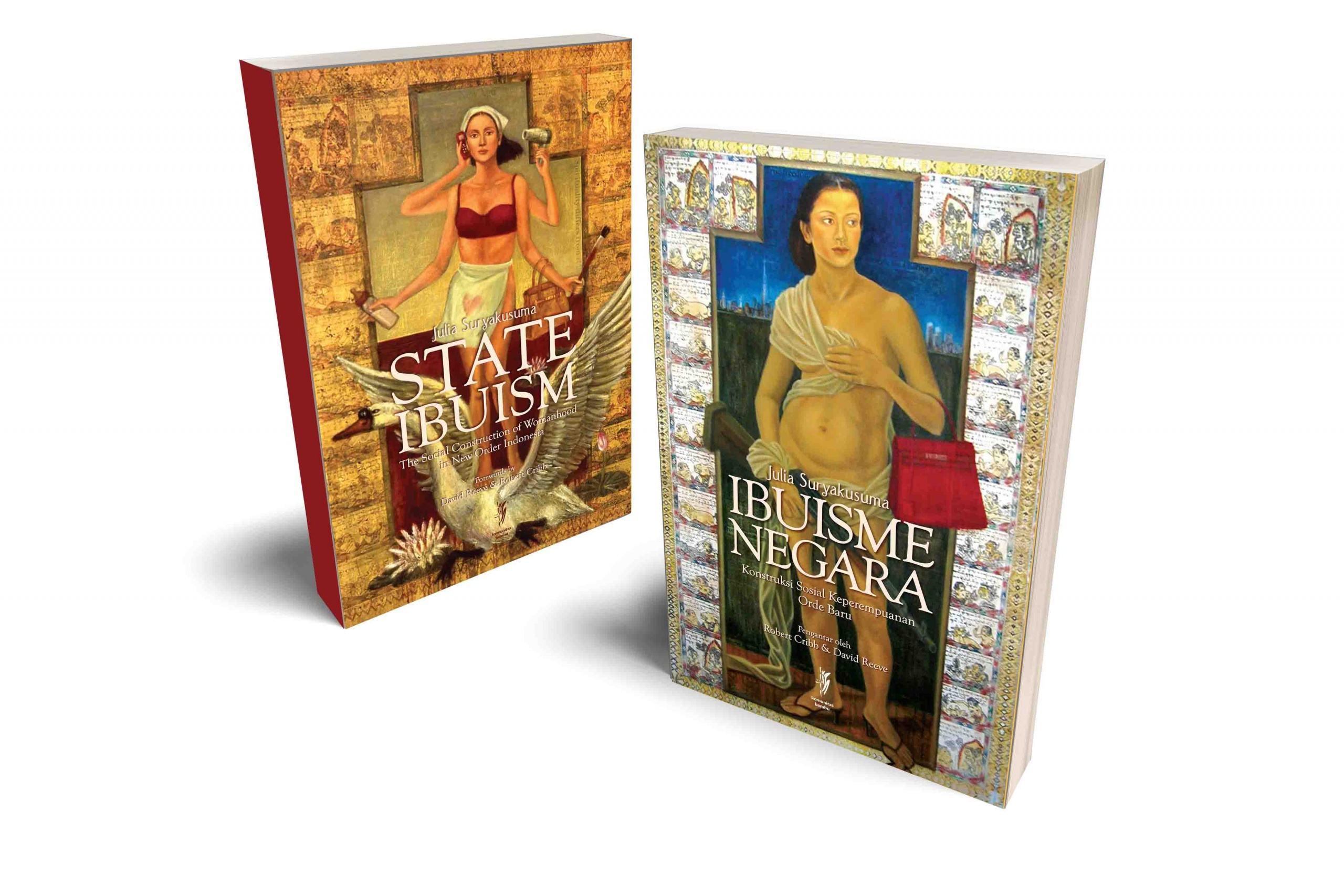

State Ibuism represents the fulfillment of that dream. The book presents Julia’s original thesis with only a few modifications — in particular, an appendix on research design has been revised and incorporated into the book as a chapter in its own right. Significantly, State Ibuism presents Julia’s thesis in Indonesian as well as the original English. This great achievement makes her insights more accessible to research communities and interested individuals in Indonesia.

In its current form, State Ibuism begins with a short publisher’s foreword explaining the history of the book, additional forewords by David Reeve and Robert Cribb; an author’s introduction by Julia herself, and the original preface to the text. All this is followed by the book’s six core chapters.

In Chapter 1, “The State and the Social Construction of Womanhood”. Julia explains her central concept of state ibuism, about which I shall have more to say in a moment.

In Chapter 2, “The Indonesian State and Women’s Organizations after 1965”, she provides a very helpful historical analysis of key governmental organizations during the new order that shaped women’s lives.

Chapter 3, “PKK, the Indonesian Family Welfare Guidance”, continues the discussion started in Chapter 2, focusing on the PKK itself.

The discussion of State Ibuism shifts in Chapter 4, “Buniwangi and Citandoh, 1984”. While best known as a feminist theorist and public intellectual, this crucial chapter reminds us that Julia’s conceptual innovations regarding State Ibuism were grounded in intensive fieldwork.

Focusing particularly on Citandoh, a rubber estate in the Buniwangi area of West Java, Julia shows us how state ideologies promulgated by the PKK and other bureaucracies shaped women’s thinking and experiences, including how these women resisted or reconfigured those ideologies.

Chapter 5, “Research Aims and Methodology”, was (as noted earlier) originally an appendix. As a stand-alone chapter, it provides valuable discussion concerning Julia’s approach to data collection and analysis, including the differing challenges of urban versus rural research. This chapter is followed by Chapter 6, “Summary and Conclusions”, which discusses implications of state ibuism.

I want to round out my discussion of State Ibuism by emphasizing its continuing significance. The editors, who thankfully brought this book to us, note that it is a “historical document”, its research and theoretical framework reflecting the late-1980s contexts in which it was written.

However, I cannot overemphasize its contemporary relevance. It should be required reading for anyone interested in questions of freedom, inequality and social justice in contemporary Indonesia. This is because, as William Faulkner famously wrote, “the past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

I hope two examples will suffice to illustrate this point. The first, outlined above, concerns my own research and indicates the breadth of Julia’s thinking. While she understandably focused on women’s experiences, she consistently emphasized her analysis was directed at questions of gender and sexuality in the widest sense. Indeed, Julia noted that her notion of ibuism (roughly, “motherhood”) could also be termed bapak-ibuism (“fatherhood-motherhood”, p. 10).

In other words, at least a decade ahead of her time, Julia was noting that the militaristic new order state was predicated not just on ideologies of masculinity and femininity, but ideologies of heterosexuality. Thus, homosexual Indonesians can, under the New Order, be seen as literally outside national belonging.

Second, Julia emphasized in her new introduction “don’t be fooled: the mechanisms and outcomes of governmental control are still strikingly similar”, and that “the dominant social construction has become an Islamic one — or at any rate, the version of Islam Muslim conservatives would like us to believe, requires subordinate, compliant Muslim women”.

By pointing to the diversity of Muslim thought, she provides us an opening to realize that the contemporary Indonesian state, including Islamic forces allied to the state, draw from the system of thinking originating in New Order state ibuism to a far greater degree than commonly acknowledged. In other words, state ibuism is not dead; it’s not even past.

A question for future researchers is thus in what ways there might be forms of “Islamic ibuism” in contemporary Indonesia that may owe more to outdated state rhetoric than any precepts of Islam itself. This is just one way in which we can continue to draw upon Julia’s rich analysis in State Ibuism, as well as her continuing intellectual contributions to Indonesian public life.

The writer is a professor at Department of Anthropology, University of California, Irvine, US.

Comments (0)